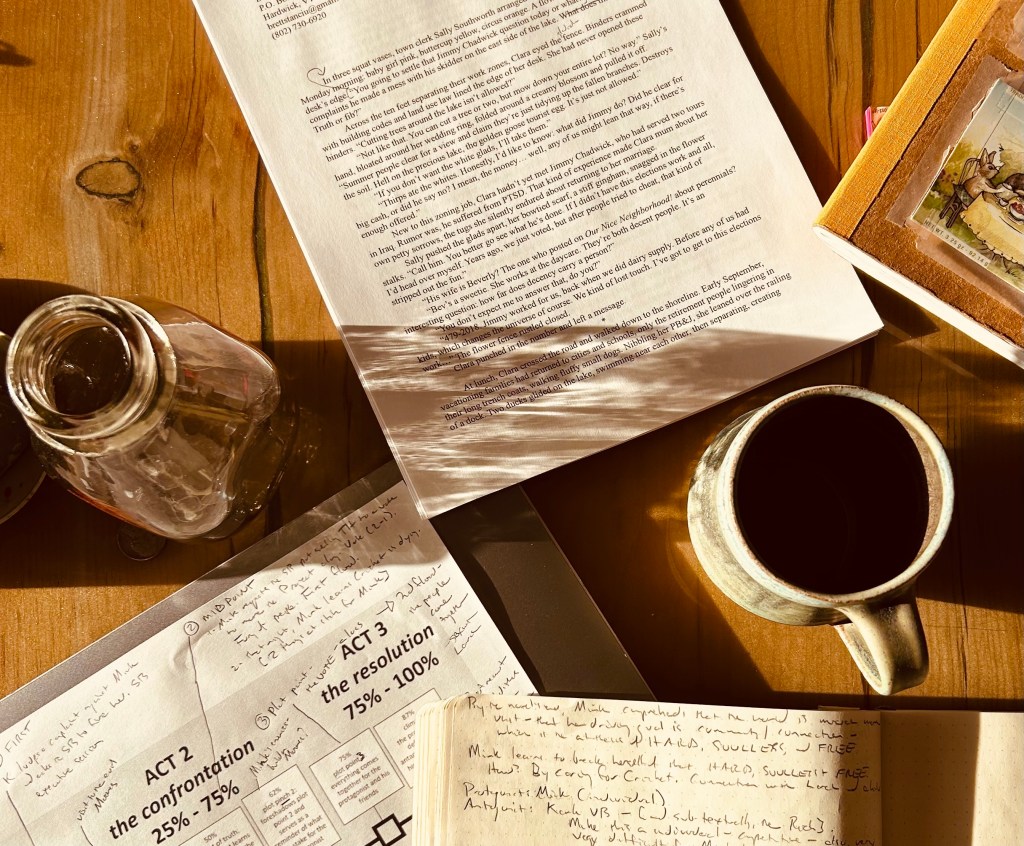

Saturday morning, I chip at my day’s list, persistent: my thousand creative words, email that shouldn’t linger, the house chores of wood and compost. On the nearby trails, I ski and later drink coffee with my beloveds, and we ponder construction that will tie up this town, Hardwick, until the sundress-wearing season. At home again, I finish the 2025 taxes, stow things in boxes, preparing for a carpenter who will remove a kitchen wall and put a window in my kitchen. This plan I hatched while I was marooned in my house for months, struggling through chemo. Now, this winter, I wondered, Am I mad? Will I still proceed? But opening the heart of my house to the view of the village seems a hopeful act, a kind of creative resistance against dismal five-year survival statistics, an act of beauty in contrast to the darkening world.

I abruptly need the sky and the muddy earth beneath my boots. I consider phoning this friend or that friend to walk with me, but I doubt anyone will jump at the sudden request. On this ridgeline road, I see a friend who quickens my blood. We walk and talk for bit about the things that nourish my winter-worn soul: about the unexpected in our lives, about writing and doubt, an April event of poetry and art and food. About what Bashō called “the journey itself is home.”

She heads home, and I keep on along the maples. All winter I’ve walked here. One frigid January, I’d gone too far and considered flagging a stranger in a car for a ride, but I didn’t. I kept on, as we all do. An eagle spreads its wings over a hayfield then disappears over a treeline. Blackbirds sing. A skunk waddles along the road. The snowbanks are above my head. The creature and I consider each other. Then, on our respective sides of the road, we each ease along. When I look back, the skunk is hurrying along, too.

Another spring. So many years I’ve lived through a New England winter, so many springs, and yet each March arrives as a surprise, a fresh reckoning. The wind smells of the opening earth. Twilight will soon be nestling in, and I’ll be home again, feeding my cats and the woodstove, eating a blood orange. A friend plans to visit, and we’ll keep each other company. Better to think of the days without names or numbers. Wiser to place these with a friend’s name, with skunk, puddle, blood moon.

You ask the sea, what can you promise me

and it speaks the truth; it says erasure.… Nothing can be forced to live.

The earth is like a drug now, like a voice from far away,

a lover or master. In the end, you do what the voice tells you.

It says forget, you forget.

It says begin again, you begin again. ~ Louise Glück