Nearing the end of soccer season, my daughter’s high school community suffers a second tragic death in just a few years. In this little rural school, the news seems almost unbelievable, except it’s not.

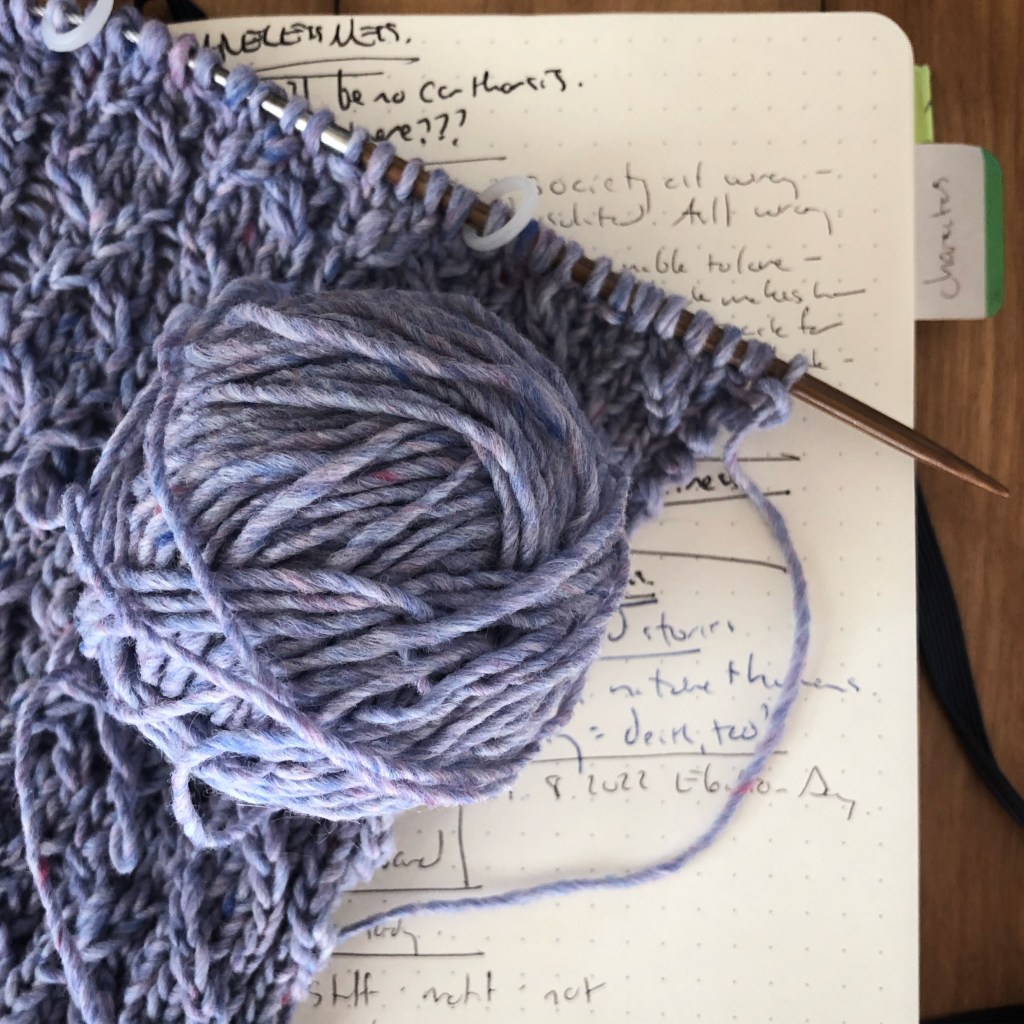

The loss is not my own personal grief, and so I keep on, of course. On a Tuesday, I leave work early and drive to a game in a northern town where I’ve never been. All morning, a cold rain had fallen. The school is in a town where a Blue Seal Feed plant dominates the shabby downtown. I appear with my knitting needles and a ball of yarn. I’ve forgotten a chair, and another mother takes pity on me and walks back through the mud to her car to retrieve an extra. I end up at the end of the row of spectators. A black cat with white paws wanders by and jumps into my lap. Beside me is a high school boy whose name I never asked who christens the cat Mittens and tells me about his cat named Turkey who was born on Thanksgiving. He speaks slowly and calmly about ordinary things like the railroad workers driving along the tracks in their trucks at the end of the workday. Cigarette smoke streams through their opened windows.

I drive home alone, missing my friend who is no longer my friend because of some certainly unforgivable thing that passed between us. Nonetheless, I miss her as I drive through the long autumn twilight. In this unfamiliar territory, I pass through farm fields where tractors are silhouetted against the sunset, through fields harrowed up black or still emerald green from the year’s final hay cutting. Mist floats over still ponds. The forests are a mixture of gold and russet, gray where branches emerge. Shot through with the day’s final sunlight, the landscape might be an 18th century oil painting.

The darkness catches up with me. At home, the cats will be hungry, the fire in the wood stove gone down to embers. I pass through a village where I haven’t been in twenty years. I had visited with a young woman both baked cakes for a living and built bridges.

As I drive through the forests and over mountains a few other vehicles pass my way — a milk truck, scattered cars. This American Life tells me stories as I live through my own American Life. Both times when Covid entered my house I felt the thinness of my life. Beneath a red-neon GAS sign, I stop for gas. My jeans are mud-splattered. Despite the drive and my car’s heat, I’m shivering although the air here, away from the sodden field and the river, feels almost balmy against my face.

I screw on the gas cap and step away from the pumps where it’s only my car, anyway, with the cardboard box of peony roots someone salvaged from their garden and passed along to me. The evening star gleams over Elmore Mountain. For some inexplicable reason, I remember stepping out into the New Mexico night the last time I visited with my brother, relishing the night’s splendor. We talked about those numberless nights camping as children, sometimes humid, sometimes frosty, in good times and bad. The night is an ancient, ubiquitous realm. Red and white lights of traffic glide along the road. I get back in my car and place my hands over the heater’s blowing vents.