An old friend and I walk through the hilly town forest, sharing the tenor of stories that are manna for my soul: which ways our lives have turned and bent, what are the elements that shape us and our families. A little sleet or maybe rain patters down on what remains of the leaves.

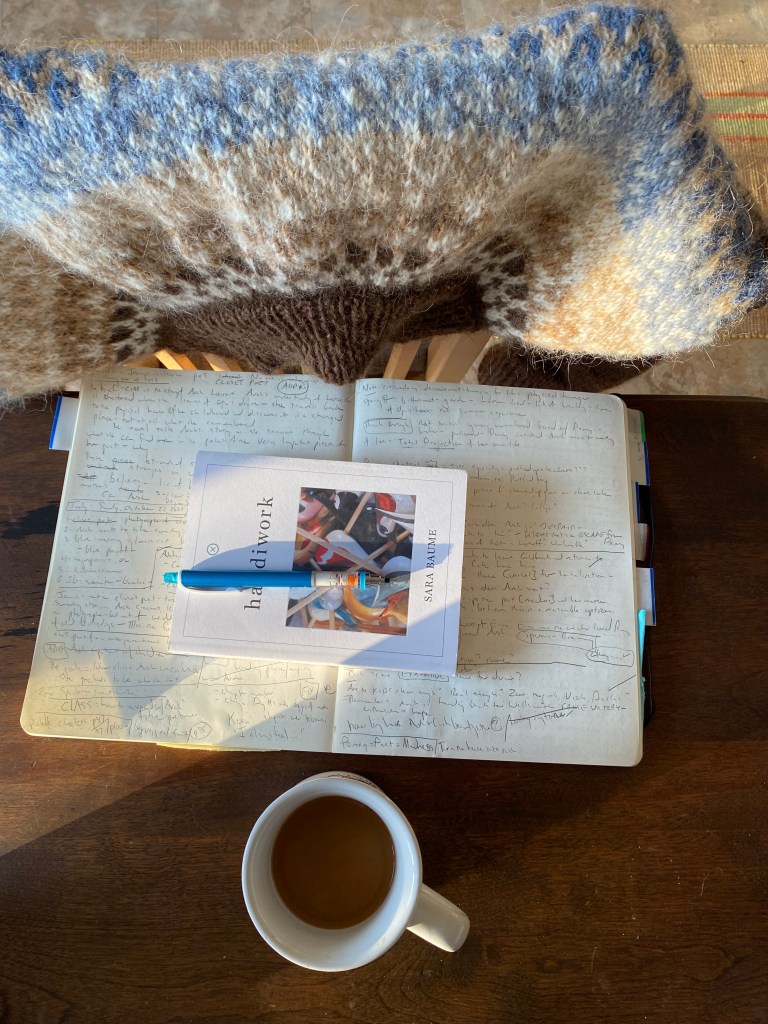

On my way home, I stop at the coffee shop and drink espresso in my damp sweater smelling of sheep — a lovely barnyard smell or a repulsive one, depending on the person I suppose. I carry my laptop and my notebook back home to my wood stove and my cats who remind me their needs are few and the most reasonable constant in this house.

By five, it’s dark as the inside of a pocket. Public radio spins in the greater world. In my tiny dining room, I pull a book from shelf and set it on the table, then another and another. In an hour or so, by then listening to This American Life about rats, I’m in the basement searching for the half-full can of Sunshine paint I used in the bathroom last winter.

Three more walls await me. I’m out of paint and decide a lime-lemon will suffice. I’ll need to drive that half-mile to the hardware store, which annoys me as I have brand-new studs on my snow tires, and why waste those on dry pavement?

All this: it’s that old familiar question, that rub between creation and destruction. Espresso and sunshine-yellow paint have never cured the world’s ills, but a slice of pleasure can’t harm.

In my bookshelves, I find a poem I printed out shortly before the pandemic nailed shut Vermont, still utterly relevant today:

Blackbirds

by Julie Cadwallader StaubI am 52 years old, and have spent

truly the better part

of my life out-of-doors

but yesterday I heard a new sound above my head

a rustling, ruffling quietness in the spring airand when I turned my face upward

I saw a flock of blackbirds

rounding a curve I didn’t know was there

and the sound was simply all those wings,

all those feathers against air, against gravity

and such a beautiful winning:

the whole flock taking a long, wide turn

as if of one body and one mind.How do they do that?

If we lived only in human society

what a puny existence that would bebut instead we live and move and have our being

here, in this curving and soaring world

that is not our own

so when mercy and tenderness triumph in our lives

and when, even more rarely, we unite and move together

toward a common good,we can think to ourselves:

ah yes, this is how it’s meant to be.