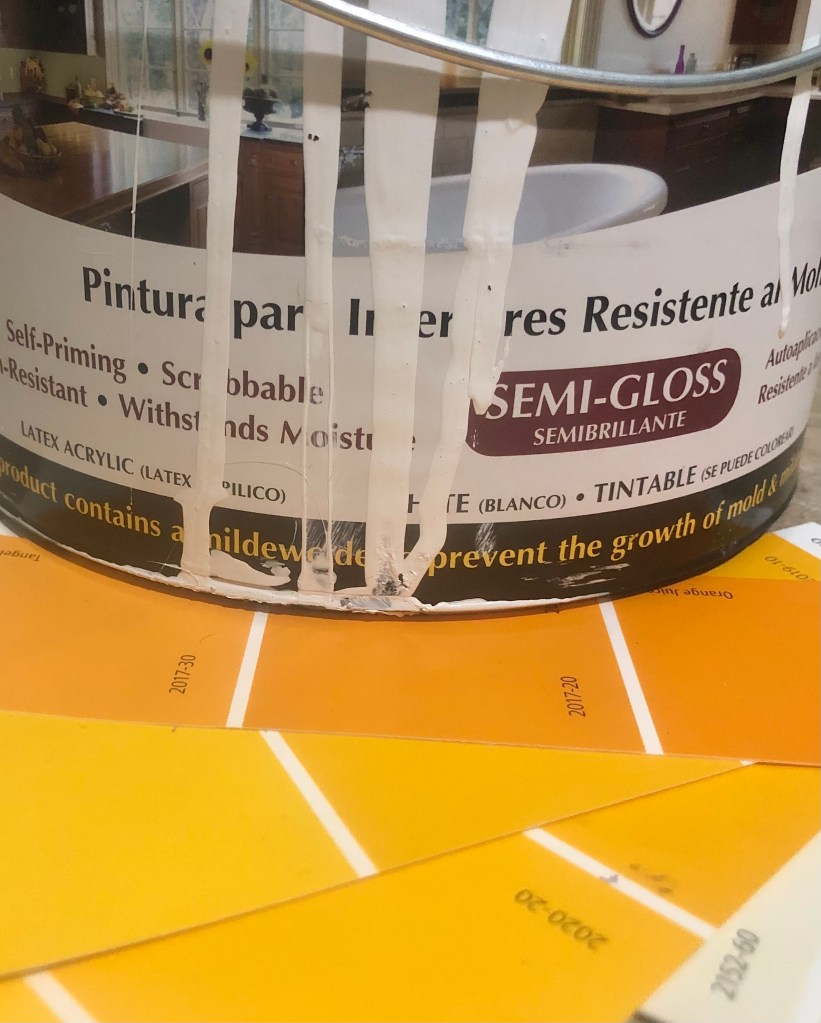

Anyone who knows me knows that winter pulls out my mania for painting. In a fit of what I can only describe as sheer irritation, I bleach mold from the bathroom ceiling and then ask for primer advice at the hardware store.

The store is darn near empty, save for two clerks and a black cat who rolls on its back on the counter and flicks a pearl-tipped tail at me. A clerk walks back with me to the paint section. She and I have been on a first name basis for years. While my gallon of primer is on the shaker, she shares her bathroom ceiling painting experience, and I offer this small problem and ask her to solve it. We walk back slowly to the front counter. She’s been my height for years, but as we walk and talk, I realize she’s slipped down below my height, and my height is definitely (as my brother might claim) substandard.

A man in logger’s chaps pays for discounted Christmas tree lights and a Twix bar and grouses about the rain and the mud, and how can there be a January thaw when we’ve had no winter?

The clerk spreads my paint samples over the counter and asks if I’ve narrowed down any color choices. She lays one finger on the color named Sunshine. “This one,” she suggests.

I gather my primer, stir stick, the lightbulb for over the kitchen stove, and head out. Ahead of me lies an afternoon of careful work, of NPR and stories from around the world, so many places hemorrhaging in ways that far outstrip my tiny mold project. As I’ve always done, I join my head and hands in a creative project. My own imagination won’t heal the world, but surely it won’t harm.