Snowglobe snow falls in the late afternoon. November light: clear and sharp. Not much warmth here, not any season for sleeping rough and roofless, but sparkling as if our world has expanded. In an inexplicable way, the light seems washed full of hope.

The summer folks have fled elsewhere, to Florida condos or back to city jobs. The gardeners and landscapers have put away their rakes and trowels. Around the lake where I walk at midday, only the builders persist in their bulky jackets and gloves. There’s so few of us in town that me wandering by is the chance to stop and remark about stick season. At the lake’s pebbled edge, I dip in my fingers. Before long, ice will rim the bank.

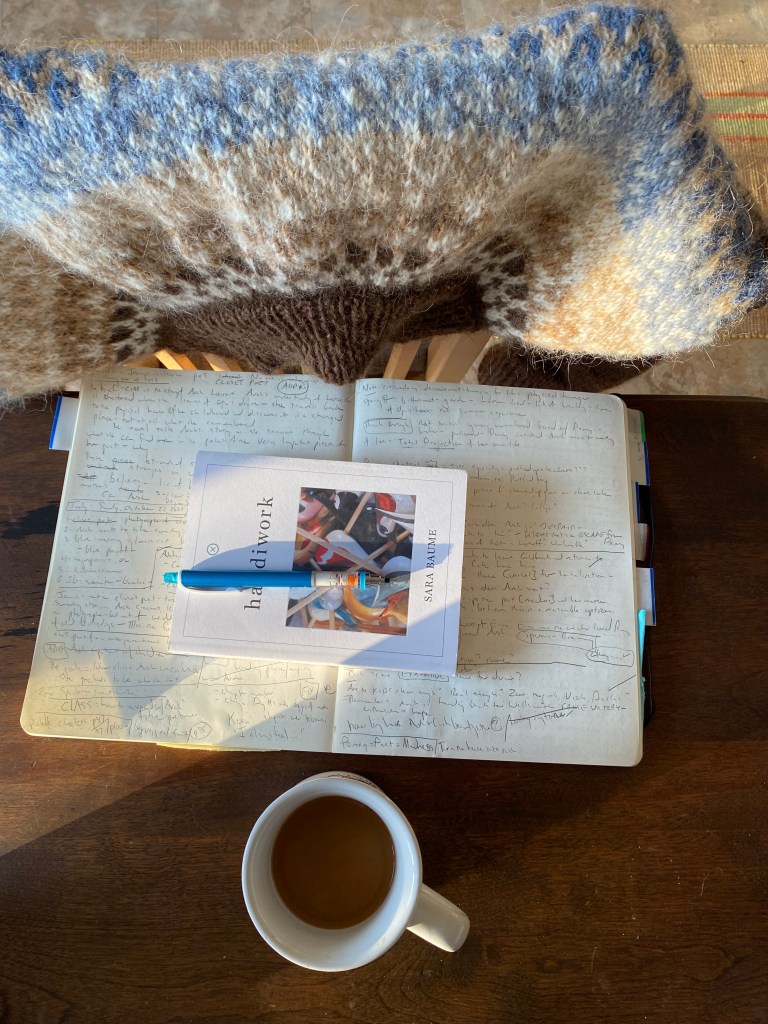

Stick season and the wood stove’s warmth make my cats deliriously joyful. Rumaan Alam (such an amazing novelist!) writes in his intro to Helen Garner’s The Children’s Bach:

Let’s agree to abandon forever the idea that the depiction of family life is the province of women artists, and therefore insubstantial. Let’s refuse to hear a sneer in the term domestic.