A friend and I stand in the high school parking lot, watching our daughters finish soccer practice on the field. At least, I say as the girls walk towards us, laughing and talking, they’ve had one practice.

That’s where we are — maybe our world will fold up again tomorrow, but at least the girls had an afternoon together, running on the field on this sunny August day.

At dinner, I quickly realize the soccer team is angry about a school board position, and my daughter glares at me. I have a seat on the board; I listen to her complaint, and think, Let her be mad at the board.

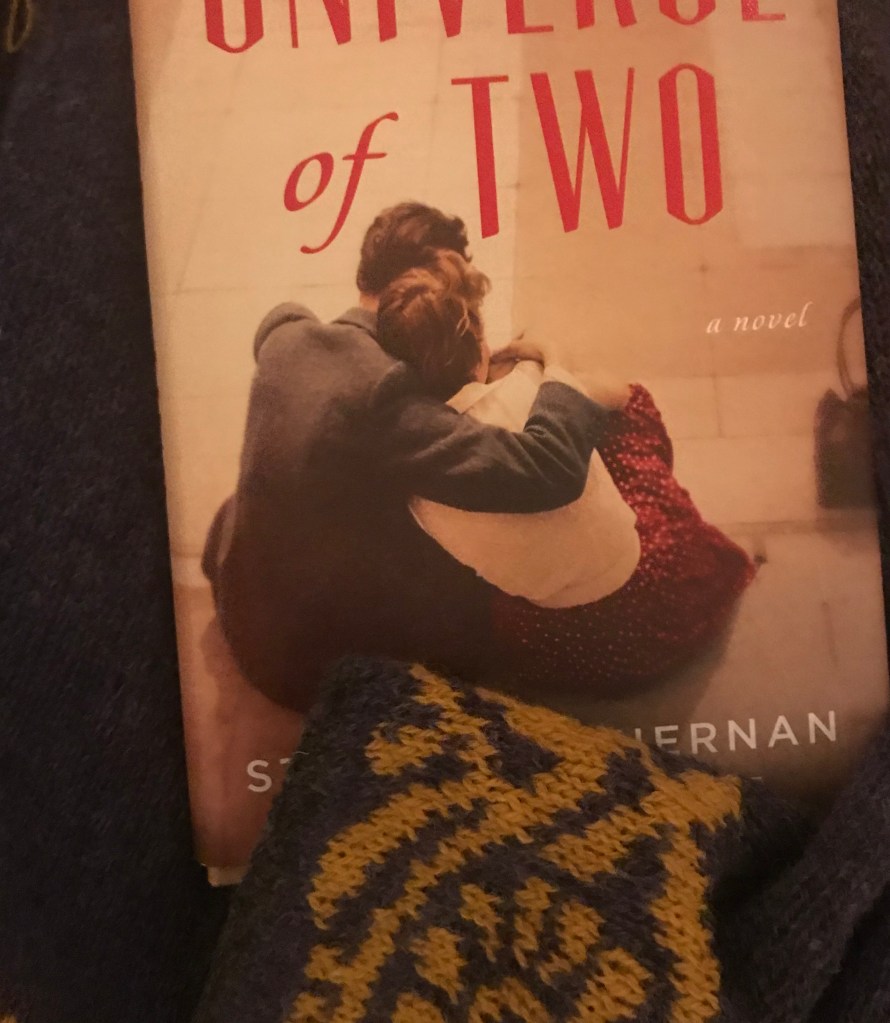

I almost don’t head down the hill to Atkins Field, for the first reading I’ve attended in months, in a beautiful post-and-beam gazebo. A strong breeze blows up, threatening rain. There’s just over a dozen of us, bundled in jackets and blankets folks have pulled from their cars, sitting in lawn chairs. I’m regretting coming, when the author begins speaking. I’ve heard this author before — Stephen Kiernan — and loved his stories. Before coming, I knew nothing about his book, but as he begins speaking, I realize the book is about Los Alamos — a place I know. I put away my knitting, huddle into my chair, and listen.

The dusk comes down. Across the way, I see a single turkey vulture flying across dark clouds, its rising wing glossy with sunset as it struggles to fly into the wind.

At the very end, Kiernan reads the opening page of his book. Kiernan reads particularly well. Listening, for just a moment, I sense all these things coming together — the craziness of attending a reading spread out with masks, unable to whisper and giggle, the ever-present pandemic, but also the setting of Kiernan’s book — WWII — and how ordinary people have endured through terrible times, and we will, too. The chilly wind reminds us of autumn’s imminence, but for these moments, the beauty and power of Kiernan’s writing pulls us together.

And when I arrive home, my daughter is waiting for me on the porch, happy again to see me.

“I met Charlie Fish in the Chicago in the fall of 1943. First, I dismissed him, then I liked him, then I ruined him, then I saved him.”

— Stephen Kiernan, Universe of Two