I park at a dirt crossroads this weekend beside a former tavern and walk up the hill to the Old West Church. The sunny afternoon speckles through the roadside maples, and I meet others doing what I am, in pairs or singly, and we greet each other, cheerily. At the Old West Church, I hear two terrific poets, but on my walk back to the tavern the line that runs through my head is from a Franz Wright poem, There is but one heart in my body, have mercy/on me, an incantation.

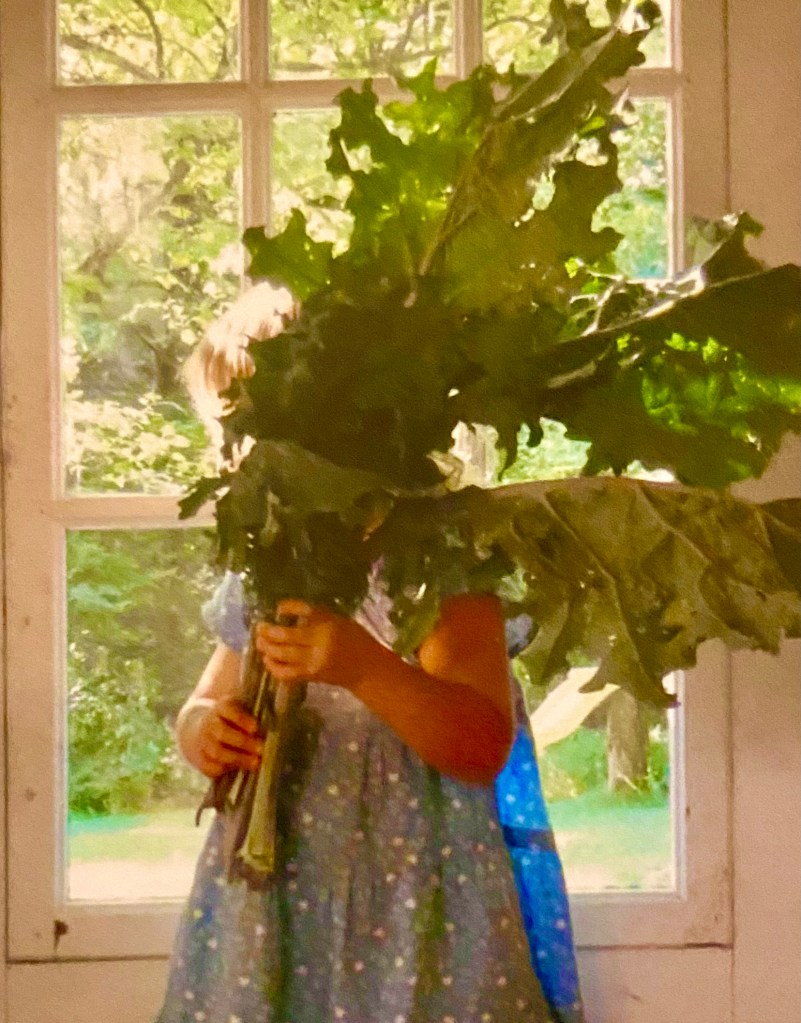

I keep thinking of my dead mother on this radiant Sunday, my mother who pulled her last breath a year and a half ago, hardly a hopscotch jump ago. In my mind, I’m building the architecture of what I’ve tagged as this Cancer Atlas I’m writing, scaffolding this book’s bones. The book is about the here-and-now, about living (at least for now) through a terrible disease, about walking along Vermont’s autumn-gold back roads, about pulling up this summer’s frost-killed pepper plants that produced so bountifully this summer. And my mother? As I work, I think so often of her, this woman both generous and mercurial, the double blade I harbor in my own heart. Gracious, how much she’d enjoy this picturesque walk. She was a woman who loved old churches, was fascinated by adjacent cemeteries, who would have relished the art in the tavern.

At the tavern, I linger in an open doorway, talking with a curator, drinking iced tea from a half-pint jar. My mother would have drunk the wine, feasted on the cured meat and seeded crackers. Dust kicks up in the road. Old friends appear, and we joke about winter’s ferocity. It’s always a crossroads, isn’t it?

“We are created by being destroyed.”

― Franz Wright