I’m standing on a dirt road, looking up at the blue sky unblemished by any smear of cloud as my friend wraps a scarf around her face, when a Subaru speeds over the crest. Jolted, I lurch to the roadside.

$750k in cancer treatments and I’m felled by wrong-place, wrong-time on an otherwise untraveled back road? Not this afternoon.

Bitter cold warnings jam the local news. In snow-drenched Vermont, February marks winter’s swing, where the daylight begins to rush back, the light tinged with warmth, suffused with this second-half-of-winter’s promise that seeds will stir again. In the meantime, I take off my mittens as we walk and talk about writing and people and the value of a precise query letter.

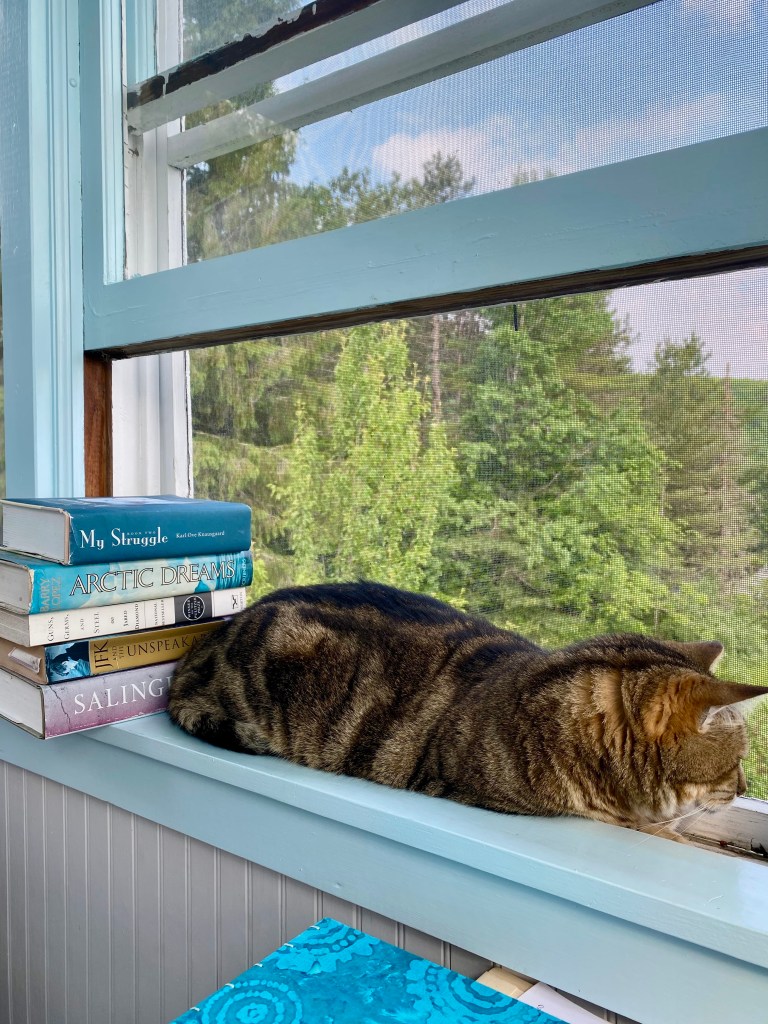

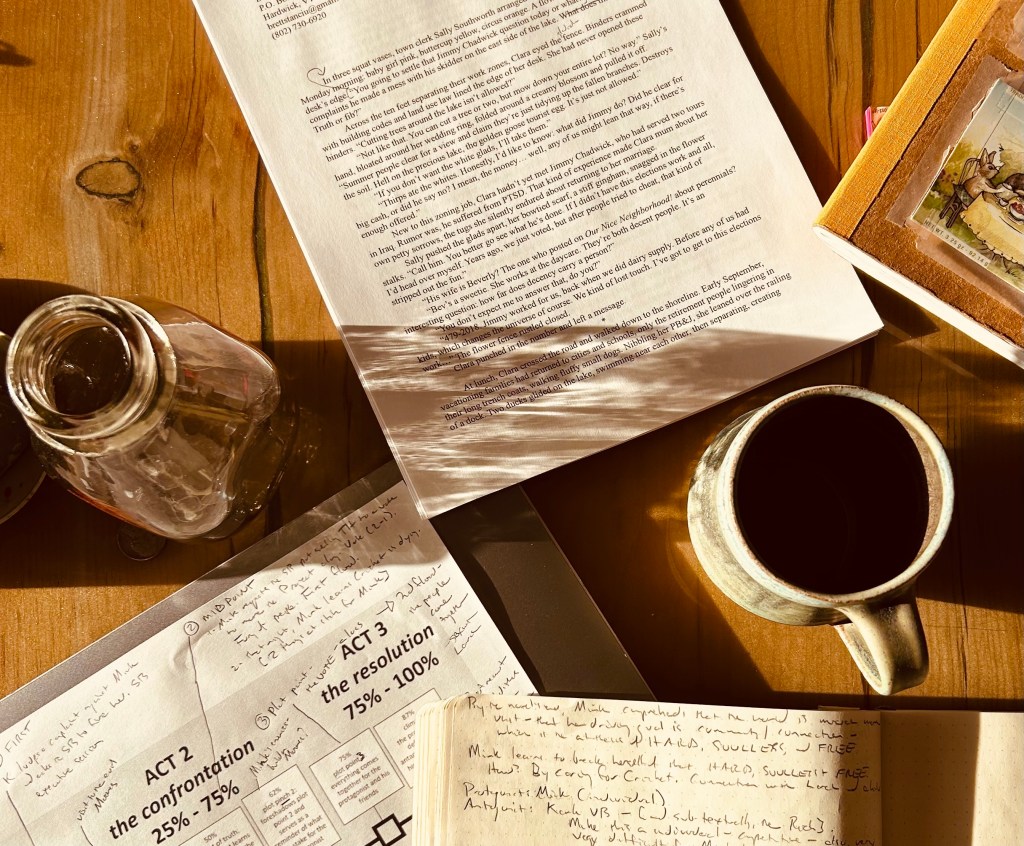

We step aside for intermittent vehicles, a silver pickup, a friend’s Prius, a Corolla with split exhaust. A year ago, I’d been sprung from a stay at Dartmouth-Hitchcock and returned to my cancer-and-chemo habits that shifted from bed to couch to what felt like a Herculean effort to open my notebook at the kitchen table and scrawl a few lines, my shaky pencil a balloonist’s line that tethered me to the world. What I didn’t know then was that the hard things I’d endured in my life, some of my making, some not so (sobriety, a divorce, selling a house and lighting out for new territory with my daughters, writing and selling books, the pandemic, the constant wear of subpar home economics), was training for the next 10 weeks. In what is now a blur of that back-and-forth from home to Dartmouth, at one point my oncologist’s eyes widened just the slightest; I wondered if my life was tapering to its end. Was my body about to be driven under?

But not last winter. Not this sunny afternoon, either. What rich luck to walk on a Vermont ridgeline road, the snowy mountains in the distance, finches in a roadside maple. To work, to share a plate of roasted salty Brussels sprouts with a friend, bake a chocolate cake for my daughter’s birthday.

I will never escape this cancer, whether I live a year more or thirty. Its fearsome and awesome power churns through my heart. How it revealed unequivocally to me the brutality and dearness of this world.

Meanwhile, as I cherish these days, these hours and minutes, the country where I live hemorrhages, the last moment of a man’s life pounding through the chaos, his words to a stranger, “Are you okay?” illuminating suppurating wounds. All the things, sadness and delight and such sorrow, the radiant sunlight. Each of us, moving along our paths: separate, together.

Be like the fox

who makes more tracks than necessary,

some in the wrong direction.

Practice resurrection.

― Wendell Berry