About 17 years ago – in what doesn’t at all seem like another lifetime but part of these continuous decades I’m living, I walked in the dark from our sugarhouse to our house with my two children. Having worked all day, I’d received a reprieve from sugaring and carried up the dinner chili pot and dirty bowls and spoons. March, the nights are always cold, although sometimes a balmy breeze stirs up as a teasing promise of spring.

I threw the kids’ soaked snowsuits in the washing machine (in those days, the washing machine was always churning) and banked the wood stove. I was knitting something from yellow yarn. What this was – a child’s cap, a gift pair of mittens – I can no longer remember. But I remember reading Maurice Sendak’s Chicken Noodle Soup with Rice to my five-year-old, who slept beside me, profoundly as a child sleeps, her cheeks flushed rosy from a day outdoors. In these hours of making syrup, the children had brought in the mail from the driveway box.

The house was warm after hours in the unheated sugarhouse and also cold, since no one had fed the fire all day. I opened The New Yorker and read “March” by Louise Glück, a poem I probably quote every March in this blog. 17 years later, I’m still reading this poem, even as that kindergartener is now a college sophomore. There’s that cliché, in like a lamb, out like a lion, but March is often lion and lamb, all the time. Now, 17 years later, less impatient with spring’s maddening dawdle, I no longer read Maurice Sendak. Yet, unlike the triteness that when the children are grown, they’re flown, our family delves into my disease, digs hard at the stuff of what family means.

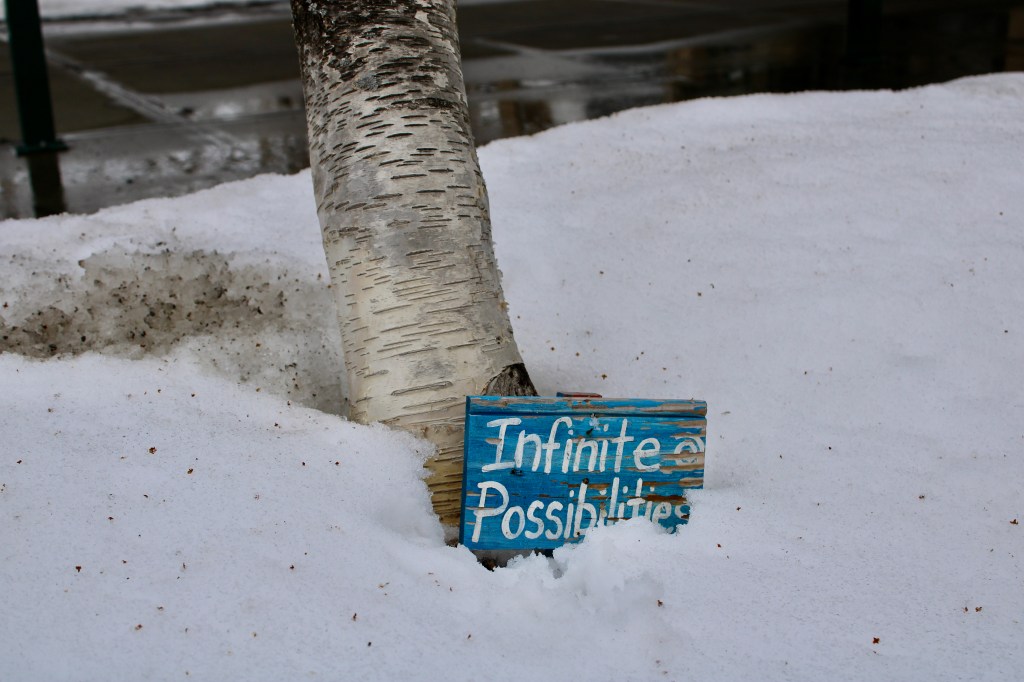

Still at Dartmouth, the nurse muses this morning about nine degree temperatures. March is a brutal tease and may leave more sharply than she arrives. But it’s March. The earth will thaw. The universe ambles along, dragging us, too.

You ask the sea, what can you promise me

and it speaks the truth; it says erasure….

The earth is like a drug now, like a voice from far away,

a lover or master. In the end, you do what the voice tells you.