My neighbor runs out his back door, shouting and waving his arms. I’m working on my upstairs glassed-in porch. He cranks up the volume on VPR’s Morning Edition. I’m guessing he hopes the young woodchucks burrowing beneath his deck aren’t NPR fans.

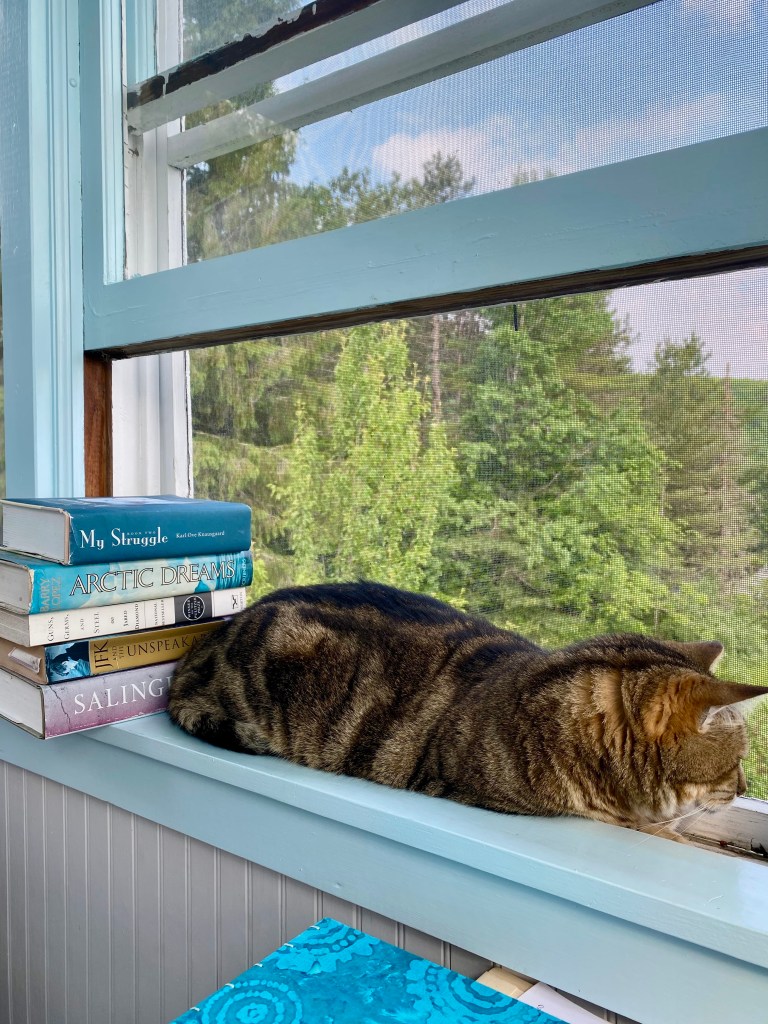

Like my neighbor, I am a VPR fan. This morning, news of Iran dominates the air. As I labor to join noun to verb, I notice my heart beating at Steve Inskeep’s words. Eventually, I leave my cat sprawled on the windowsill and head downstairs to wash the dishes. I’ve listened to NPR my entire life. Heck, the radio was probably playing when my parents brought newborn me home from Presbyterian Hospital in Abuquerque. Little these days is good news.

This winter, I’ve written in this space about my obsessive struggle to remain among the living on this planet. Only now—two surgeries, six rounds of chemo, 11 hospitalizations later—do I realize the diciness of my determination to live. A few weeks ago, driving with my daughter, she showed me a lawn where she cried on a bench because I believed my mother would die. Every day now, as I begin by feeding my two cats and drinking coffee, I carry this winter, those months of spitting distance from my grave, within me. As at the beginning, my greatest worry was/is my daughters. So many months later, I understand how my life is connected intrinsically to so many others. That what lies before my eyes are the twig tips of stories.

In my younger, brasher years, I might have written about politics and conflict, but the Mideast is a place I’ve never been, with people I’ve never met, for whom I will never speak. Too, I’ve knocked around this planet long enough to know that violence changes the world, irredeemably. That the combination of deceit and anger and hubris wrecks destruction. And that cruelty wrought can never be undone. We hurtle onward. I keep listening.

June, and pink roses bloom against my house, planted by someone I never knew, perhaps the woman known as Grandma Bea buried in the adjacent cemetery’s crest. My daughters climb a mountain with a view of Vermont’s shimmering Lake Champlain and the emerald patchwork of farms stitched together. They return with a gift for me, a thorny rosebush with fragrant blossoms that fill my cupped hand. In the evening, shortly before dark, I walk in my bare feet, the long grass already cool with dew. High heat is predicted, the planet is surely burning up, but this ruby-and-gold sunset drags in a coolness. Lush, so lush this month. The butternut tree I planted stretches towards the apple someone else carefully cultivated and noted in pencil on the barn’s bottom wall. A record someone held dear.

In 1956, Allen Ginsburg wrote: “America this is quite serious.”