William Maxwell writes in his riveting short novel So Long, See you Tomorrow: “The reason life is so strange is that so often people have no choice.”

This strange world, indeed. My daughter drives us up Vermont’s long loneliness of I-91, the interstate running above the river. Villages are tucked into the blue and snow-sprinkled mountains, these tiny clusters dominated by spires of white clapboard churches. This has been a week of in-and-out of ERs and hospital rooms, of resurgence in energy and a low so low I’m unable to bother to speak. Now, the ride home, the passing through of this winter country, where the new snow (so pure white) piles high on tree branches. This northern land in midwinter is territory I know with a familiarity akin to the veins on the backs of my hands. A haven of cold, often slow-going, a muted palette of pale blue, sooty gray, evergreen nearly black.

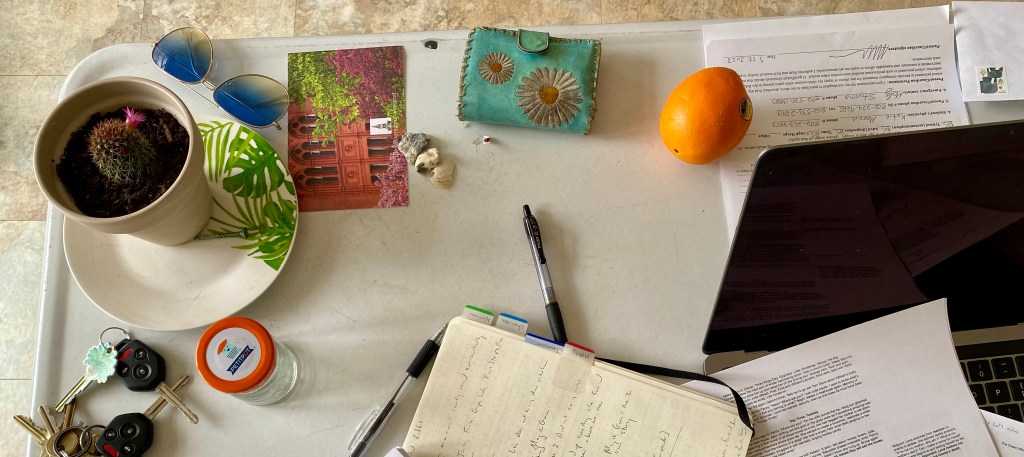

We talk until we’re spun out from chatter. I lean my head against the cold Subaru window. In the last room where I stayed, my companion was a woman born in 1933. 1933 marked the end of Prohibition, the year stenciled on the green-glass-bottled Rolling Rock beer we drank in college. 1933, the year of Roosevelt’s New Deal. The woman’s voice was clear as a spring stream, often studded with small wry jokes. When she saw me, her face glowed in a smile. Of all the things I’ve learned from this week and scribbled into my notebook, this woman’s radiant smile and easy language sticks with me. A few times, I wandered her way, hoping to have some of her joy rub my way.