Right at the solstice, frost.

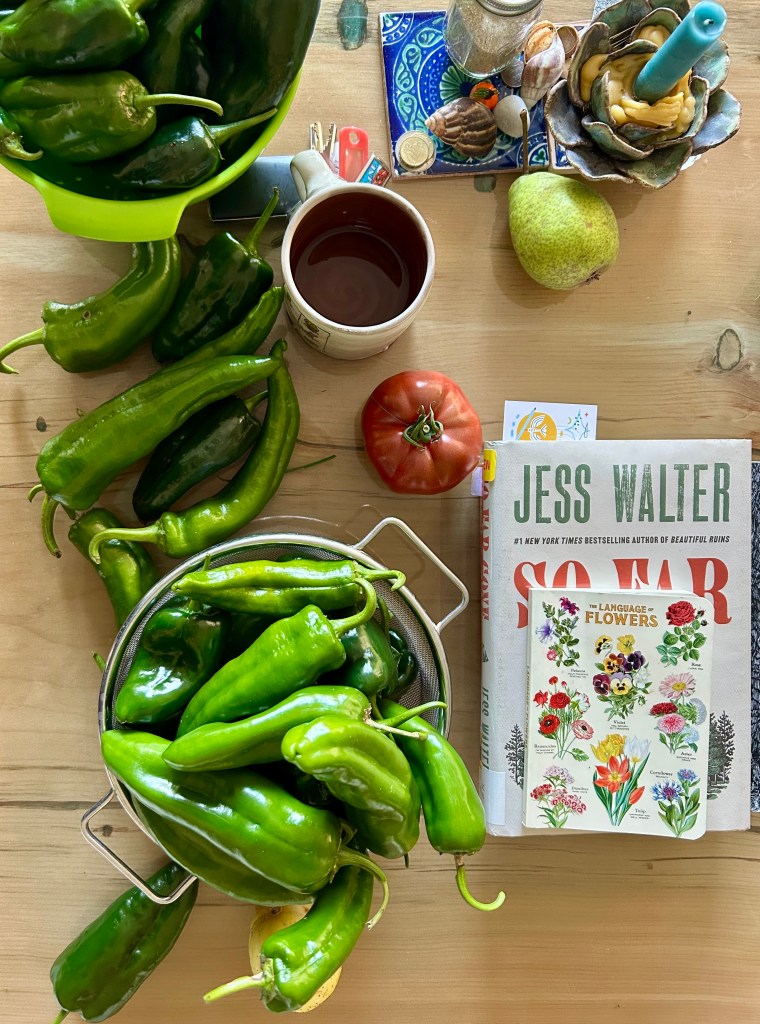

My garden planting this spring was a combination of friends who appeared and weeded and planted, of the sunflower seeds I sowed and the woodchucks ate and I replanted and the woodchucks devoured again, of volunteer calendula and love-lies-bleeding and towering gold sneezeweed, and the pepper plants from a friend that produced in enthusiastic abundance.

Hurray for the garden. These evenings when I light the first wood stove fires of the autumn, my cats chew shreds of birchbark, sprawl before the warm stove. Hurray, they purr in their cat way.

Season’s change again, so familiar and yet different, each day fresh and welcome. Season’s change for me, too, some days filled with friends and colleagues, other days I hole up and get my work done. Writing now about cancer, I imagine holding this keen awareness of my mortality, of the perishable world, in my hands: a tender-eared rabbit, a vicious rat, or maybe simply a handful of sunlight.

In the deep fall

don’t you imagine the leaves think how

comfortable it will be to touch

the earth instead of the

nothingness of air and the endless

freshets of wind? And don’t you think

the trees themselves, especially those with mossy,

warm caves, begin to think

of the birds that will come – six, a dozen – to sleep

inside their bodies? ~ Mary Oliver