Under the waxing full moon, January’s hungry Wolf Moon, I hurry along in the few degrees above zero. I’ve forgotten my scarf, so when I turn and lean into the wind, I cover my cheeks and lips with my mittens and breathe in the scent of wool. It’s too cold for wetness, yet my mittens are redolent with sheep.

The wide sky and the fierce cold winnow me to shivering bones. Nonetheless, I walk further than I’d planned, thinking through a piece of writing, and then, so cold, words abandon me for images, then those, too, vanish, and it’s me in my boots and that good down jacket and the mittens just beneath my fluttering eyelashes, and intermittent pickups passing, their drivers lifting their hands silently.

My life flickers as a candle flame in my curved ribs. What great fortune to be walking along the earth’s curve as the planet bends into twilight, the ancient moon electrifying the new snow. By the time I return to the village, it’s not long after five and the darkness has settled in for the long go of the night. Nonetheless, it seems to me these wintry days are gradually lengthening. I mail a letter at the post office and then talk with an acquaintance for a few minutes in the co-op, a waxed bag of curry power in one mitten, an onion in the other. At the last moment, I remember to buy milk for the morning’s coffee.

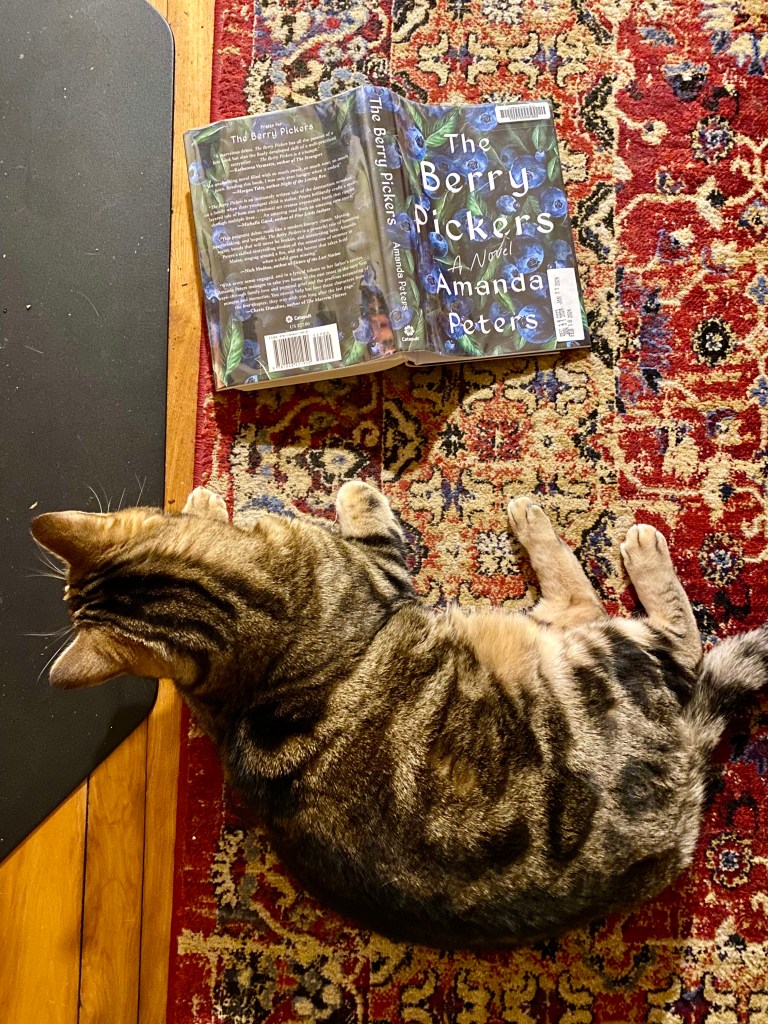

Winter. This starkly elegant season, straight-forward, no fussing around. A librarian friend passed me Andrew Miller’s The Land in Winter, a novel I’d longed to hold and read. A book of my soul. My cat Acer, eight-years-old, has discovered the pleasure of purring. We lie stacked on the couch—me, this tabby, library book—content. Who knew this was possible, my slow learner cat, my slow learner self?

“And though he was not much given to thinking about love, did not much care for the word… it struck him that in the end it might just mean a willingness to imagine another’s life. To do that. To make the effort.”

― Andrew Miller