I walked into work yesterday morning with a woman who didn’t grow up in this country. She’s learning to drive, an oddity here for a woman in her thirties. In rural Vermont, just about every kid – usually long before the requisite 16-years-old – drives.

Although like most Americans I’ve had a romantic fling with the happy motoring years (just how many times have I driven around the country?), I told this woman part of me longs to hang up the keys and know the earth only through the soles of my boots.

Our world is so overly, crazily full of images – mine as much as anyone’s. As one kind of antidote, our after-dinner twilight walks are as much about the walking and conversation as wandering through the lingering bits of daylight and spying the first stars twinkling overhead. Spring, drenchingly wet, raw, gloriously full of minute surprises, tugs us.

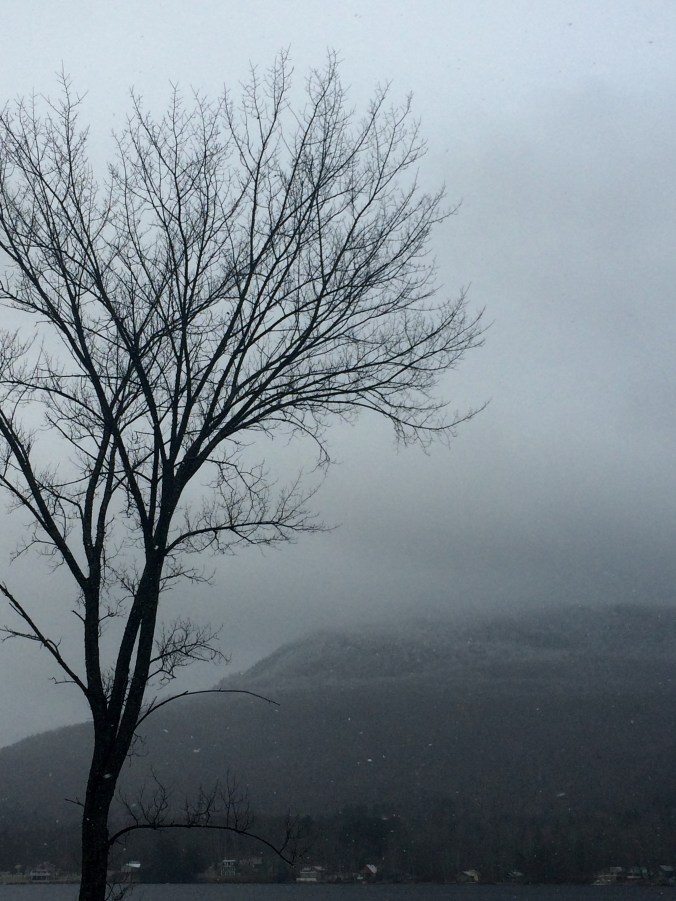

Last evening, my younger daughter and I stood outside as the cool night came down, listening for the peepers. These tiny creatures haven’t stirred in our neck of the woods yet, but the streams tumbled melted snow, in a steady song, to Lake Champlain.

My sister-in-law is a painter, and I’ll say, how long did it take you to paint that painting. She’ll say, It took me maybe three days, but it took me all my life to get the skills to paint that painting.

– Anthony Doerr