One of the more harrowing experiences I had recently was offering up testimony in a county courthouse. In a large, wood-panelled room with no windows, separated from the landscape I know and love – my children and the dark-green mountains where I live, the world of singing crickets and flower petals easily frost-bit, the sky sprawled infinitely overhead, I was asked to give my story.

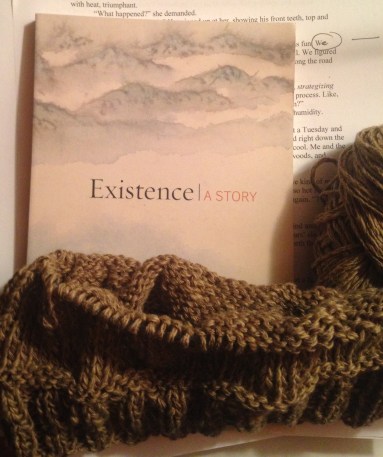

What’s in each of our own, unique stories, anyway? Breath, thought, memory: words from my larynx spun from the slender bends of my ribcage. To return to David Hinton’s Experience again, while speaking I realized how keenly our stories are presence surrounded by absence. Into this unknown world, I told my story of fear and love, my presence filling that space. In this 21st-century American world, we’re accustomed to defining ourselves in terms of our acquisitions: degrees we hold, a dwelling, occupation, the clothing we choose each day, political beliefs we cherish, whether we raise our own meat and vegetables or buy boxed foodstuffs at Price Chopper. Pushed up the against the razor’s edge of the void – through illness or a turn of misfortune we’ll all experience – we’re left with only a body created from carbon and calcium, and the immaterial thread of our story.

Our stories, always imperfectly told, are not a reflection or mirror of who we are. The stories are who we are. Hand-in-hand with telling our stories is that persistency of doubt. Is this true? Is my story worth telling? For a writer: why write, anyway? The answer, perhaps, may be as simple and raw-edged as this: because at our hearts, we are but the conjoining of body and story. In the face of the void that courthouse morning, my story hooked into strangers’ stories, as my story now weaves into yours, and yours winds into others.

In Chinese with its empty grammar, Absence appears as the space surrounding the ideograms, and ideograms emerge from that empty source exactly like Presence’s ten thousand things – a fact emphasized in the pictographic nature of ideograms, and no doubt the ultimate reason for that pictographic nature. Indeed, the ideograms are themselves infused with that emptiness, as they are images composed of lines and voids, Presence and Absence…

David Hinton, Experience: A Story

Elm Street, Montpelier, Vermont